A History of Latin America in Three Grapes

When we talk about Latin America, the geographic boundaries are enormous, containing landscapes that vary from tropical rainforests to tundra. The social geography, combining indigenous peoples and centuries of human migration from virtually every continent, has resulted in a collision of influences on traditions, the arts, and especially cuisine, difficult to simplify or summarize by any single narrative.

As we continue our countdown, the Latino Wine Company endeavors to explore the history of how Latino wine came to exist in the first place. This will provide a bit more insight about the origins behind the carefully curated inventory in our store. We invite you along with us to trace the flow of Latino wine from its ancient sources all the way to our glass and yours. So sit back and enjoy the adventure with us – salud!

From Las Canarias to El Caribe: One grape with many names

Known as the “country grape” país, criolla, misión, or Listán Prieto, this grape made its way around the world as human civilization became ever more maritime.

Archeological evidence suggests that the earliest human practices of wine production using grapes emerged in the Levant as early as 7000 BCE. Chinese rice wine production is even older. Overseas trade facilitated the expansion of wine throughout the Mediterranean into the Greek empire, and then the Roman one. This established grape cultivation for the first time throughout present-day Italy, France, and Spain – and the birth of the terroir. With the rise of the Roman Catholic Church came the primitive industrialization of the wine industry in these regions, with monasteries springing up in the first centuries of the Common Era to create the earliest infrastructures in some of the world’s most lucrative wine regions today.

Fast forward to the heyday of the Spanish empire. Las Canarias, an archipelago in the Atlantic off the West-Saharan coast of Africa, was a strategic location for the fleets of ships traveling from the Iberian Peninsula on their way to Africa and the so-called New World.

Map of Las Canarias – the Canary Islands. The archipelago is less than 1000 km from the coast of Morocco and the Western Sahara. (Source marked for reuse.)

The Castilians dominated the Canarias and controlled the flow of resources. The cultivation of sugar, then wine from Listán negro, helped sustain a single-crop economy on the Islands, vital for trading with other European powers such the British. This agricultural model foreshadowed the methods that would also be attempted in the New World colonies.

Following Columbus’s accidental arrival in el Caribe in 1492, ambition to spread both Empire and Church (and subsequently, wine) soon reached the Atlantic shores of the Americas. The conquistadores relied on large quantities of the fermented grapes as a source of hydration throughout the voyage.

Columbus sends a boat to the south of Hispaniola, 1494 (Colón envía bote al sur de Española). (Source marked for reuse.)

Realizing that transporting enough wine from the Old World to support their consumption could get quite expensive, they soon set to work taking vines with them to plant and cultivate. The most convenient varietal available, vitis vinifera, arrived to the Caribbean and spread throughout Mexico and California, where it became known as the misión or mission grape, and also making it all the way to farthest reaches of the Southern Cone, into the Patagonia. In Chile, it would be called país or country grape, and in Argentina, criolla or creole grape.

This grape is thought to have spread for its resiliency more than its elegance. The hardy grape could stand up to cultivation in any climate and fulfill the constant demand of for a consumable wine for widespread rituals such as the Catholic Mass. Criolla, misión, and país dominated the wines of the Americas from la Conquista until the 1800s, when finally the varietals on the continent began to diversify following an influx of French varietals.

Because of its vernacular origins, fine winemakers had disregarded these grapes as a varietal capable of making world-class wines, until now. País specifically is making a comeback in Chile, along with some other grapes formerly disregarded grapes including Carignan and Cinsault, signaling a new movement to both investigate the heritage of the industry on the South American continent more deeply as well as refreshing the flavors on the scene for consumers. Also, the Canary Islands continue to produce amazing wines blending Listán negro with other varietals, all topped off by the essence of their volcanic soil. Grand Cata had the pleasure to meet with the winemakers behind Suertes del Marqués from the island of Tenerife. We look forward to showing you some of their exciting bottles and more in the store.

View of the vines in La Orotava, the valley in Tenerife, Canary Islands where Suertes del Marqués is produced. (Photo courtesy of Suertes del Marqués).

Of Pisco and Potosí: Muscat

Just as grapes and alcohol aren’t only about wine, the history of Latin America isn’t only about Europeans. The ability of indigenous peoples of the Americas to resist and thrive in spite of multiple and enduring affronts since colonization is never recognized enough. The customs that exist today are just as much derived from the cultures and knowledge first present on this continent as they are from any other source. Fortunately, there are individuals working tirelessly to both recover and champion this conocimiento.

Indigenous people across the Americas produced alcohol long before the arrival of Europeans to the continent. Various kinds of semi-clear spirits, chichas, or undistilled aguardientes produced from the fermentation of fruits and grains illustrate these native traditions. Fermented agave, for example, yields pulque, the indigenous Mesoamerican predecessor to distilled mezcal and tequila.

Pulque store in Tacubaya, Guanajuato, Mexico, ca. 1900. (Source marked for reuse).

Reportedly, getting drunk on pulque was a strategy for oppressed Nahuatl people to resist forced labor under the encomienda system. The history of chicha in South America follows a similar narrative. According to Alcohol in World History by Gina Hames:

“Chicha, or corn beer, was a staple drink in the Andes. Much like pulque, it had been used for ceremonial purposes throughout the period of Inca rule and before. After colonization, however, the Spanish believed that many problems arose because of excess chicha use by indigenous South Americans.” (page 60)

In the Andean region, an interesting fusion occured between the legacy of these native drinking traditions and the Spanish insistence for grapes with the cultivation of muscat. Muscat is one of the oldest white grapes and a predecessor to Moscatel Romano, also known as Argentine Torrontés. The invention of pisco in Peru and Chile and singani in Bolivia from the muscat grape emerged as brandy-like spirit solutions that reconcile the preferences of the two cultures. As Pisco Elqui Chile writes in “The Work of the Grape and the Tradition Pisquera”:

“While the [pisco] product was derived from the grapes imported by the Spanish, its production followed the [native] Andean model.”

The indigenous etymology of their names signals their underlying heritage. The word pisco derives from either Quechua or Mapudungun and singani from Aymara. And while you may have heard of the pisco sour, recipes for singani cocktails such as yugueño and sucumbé further illustrate the lasting cultural influence of thousands of Aymara and Afro-Bolivians in the area who endured slave labor, high altitude, and harsh conditions in the Spanish controlled silver mines for almost 300 years.

Demand for pisco and singani surged in the late 1500s when the silver mining industry took off, specifically near Cerro Rico de Potosí, Bolivia. This boom was so significant that in 1573, Potosí’s population bested Paris, Madrid, and Rome and equaled the population of London.

View of Cerro Rico with modern Potosí in the foreground. The mountain was thought to be made of solid silver. (Source marked for reuse)

Muscat production to meet this demand would prove more sustainable in the long run than the extraction of silver. By the 1800s, silver from Potosí was absolutely depleted, but the industry surrounding this Andean liquid patrimony still thrives today. An Appellation of Origin for singani was even established and ratified by the Plurinational State of Bolivia in 1992.

The special origins of pisco and singani are too significant to be covered in this post alone and we’ll be revisiting their rich histories in depth soon. Whether you’ve had the pleasure to try these distilled muscats before or it’s the first time you’ve heard of them, we have some surprises in store surrounding these spirits that we can’t wait to share with you, such as Singani63 and Waqar pisco, pictured below.

Europeans Seek Revival in the Southern Cone: Tannat

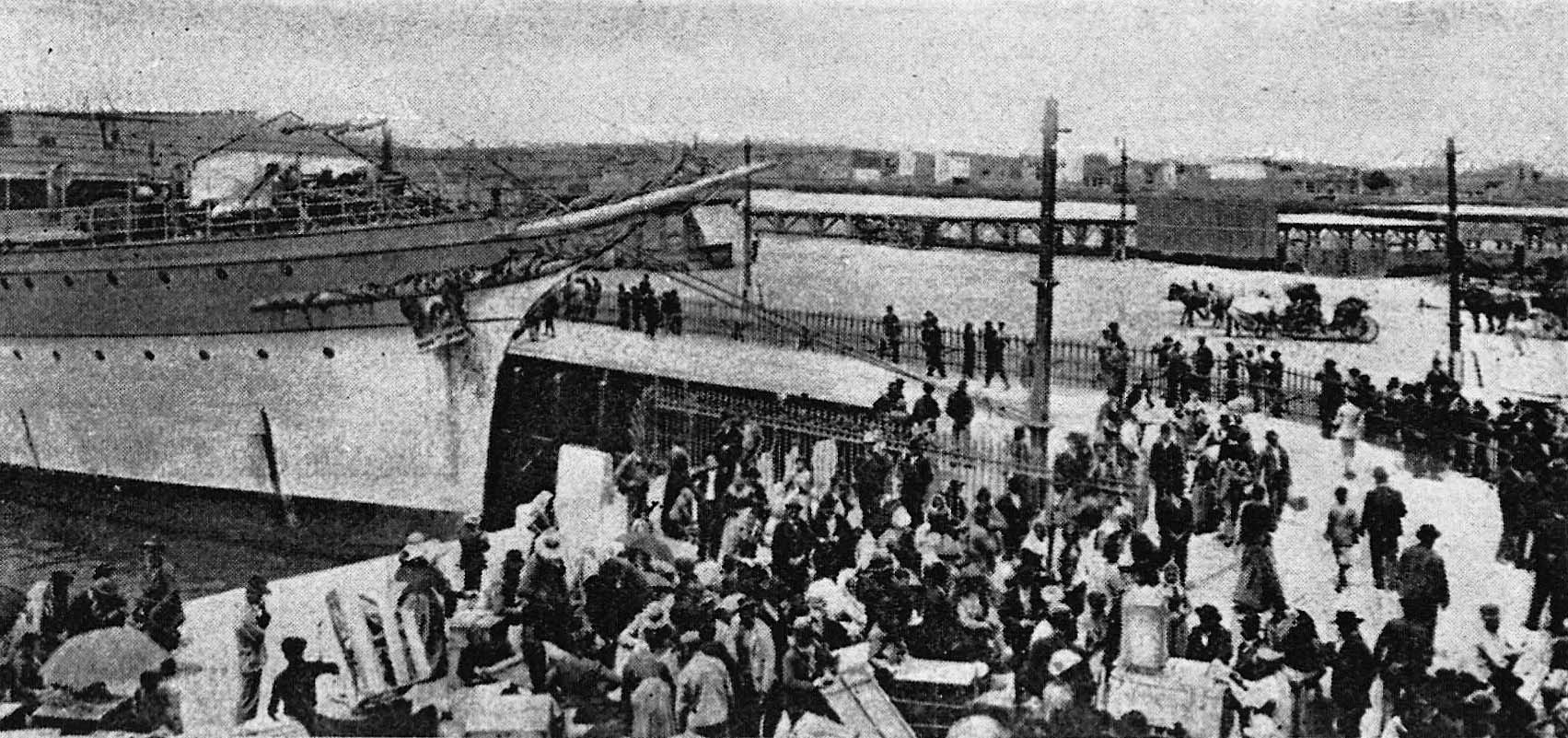

One of our modern perceptions of the Americas is that it is a land of immigrants. Spanish, Italians, Germans, and Eastern Europeans who disembarked in the ports of Buenos Aires and Montevideo, just to name a few, would inevitably leave their mark on budding national customs and cultures. Following the industrial revolution and related sweeping changes in the early 19th century, conflict, desperation, and crisis drove thousands of Europeans across the Atlantic in search of a new life.

Immigrants disembarking in the south port of Buenos Aires, early 20th century. (Source marked for reuse.)

Newly established governments across the Americas also invented various initiatives to attract European settlers to defend their young independent states from the claims of others, as well as to develop and improve local resilience. In many cases, this blend between economic necessity and lack of structure created the perfect setting for groundbreaking innovations in traditional industries.

The wine industry was no exception. A pioneering spirit would change the face of wine production in the Americas, transforming a few otherwise disregarded French grapes such as Malbec and Carménère into the leading varietals of Latino wine today. However, this is the story of the underdog: Uruguay’s national grape, Tannat.

Don Pascual Harriague in 1880. (Source)

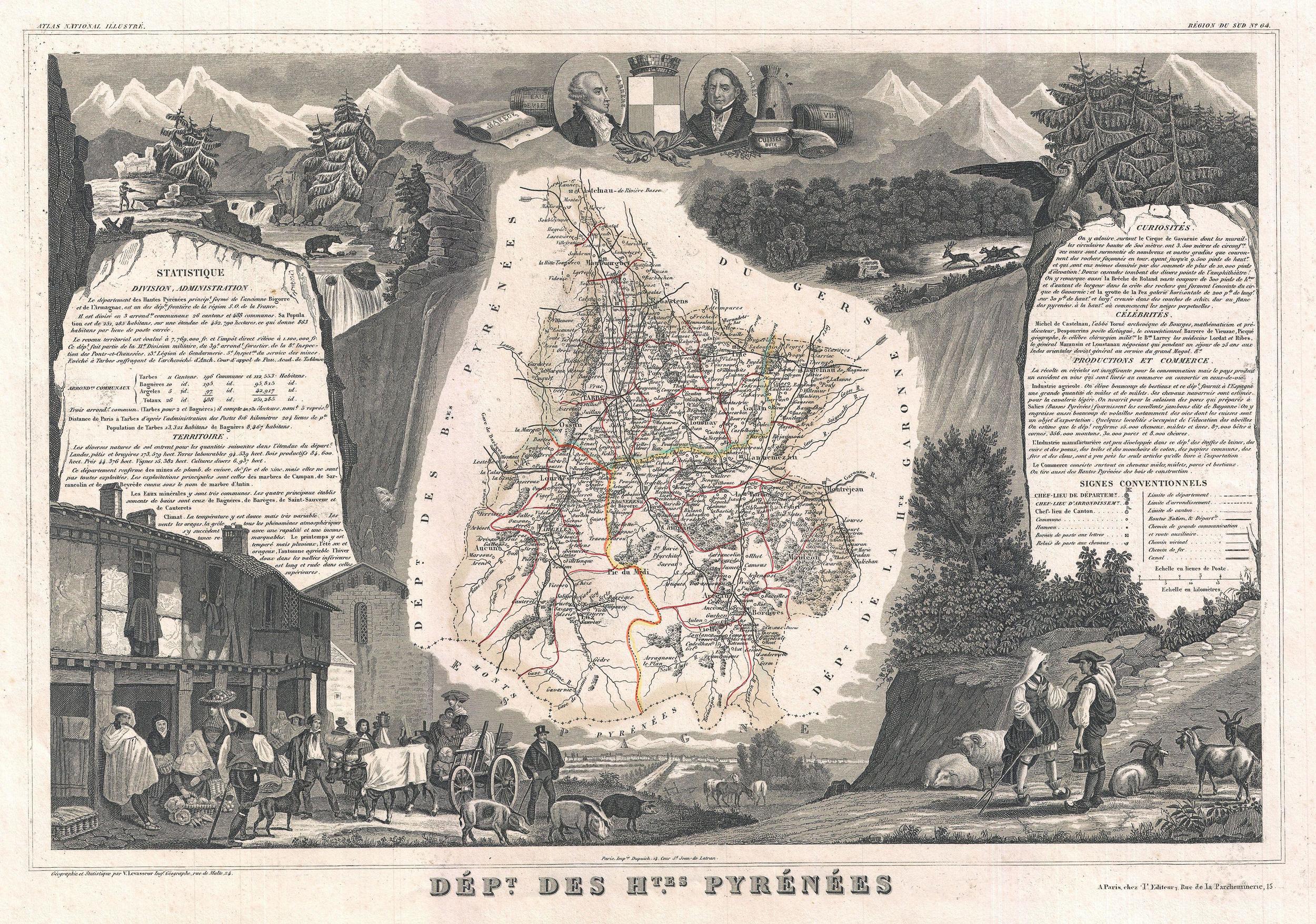

In 1819, in the foothills of French Pyrenees, Don Pascual Harriague was born. At age 19, the young Basque man set out looking for work. He ended up in Montevideo, working in saladeros and graserías, factories that processed animal products such as meat, skins, and fats into consumer goods. By 1860, he founded his own Saladero de la Caballada, in Salto, Uruguay, a town on the Argentine border. Ever the entrepreneur, he began learning about grape cultivation around this time. But the results from the readily available criolla grapes weren’t much to his liking. In a twist of fate, he met a fellow Basque immigrant Juan Jáuregui, who offers him cuttings he’d carried from their shared native Pyrenees region.

Map of the Hautes Pyrénées from 1852, near the area in France where Uruguayan Tannat likely originated. (Source marked for reuse.)

Don Pascual experimented with the cuttings and discovered them to be perfectly matched for Uruguayan soil and climate, so he began cultivating them on a large scale, devoting the terrain of his factory to their production. In 1876, he yielded his first harvest: 35 hectares of Tannat. And with his harvest, the Uruguayan wine industry was born.

Soon the production of Tannat increased and spread throughout the country to the areas of Montevideo and Canelones, the leading areas of Uruguayan wine production today. Harriague’s wines even found their way back to Spain and France where they were tasted to acclaim – earning a silver medal at the both the Barcelona World Expo in 1888 and the Paris Expo in 1889. Don Pascual was also awarded a gold medal of patriotismo to recognize the significance of his advances in defining a unique Uruguayan vini-dentity, allowing the small republic to shine on its own alongside much larger rivals on the world stage then as it continues to do today.

Uruguay's unique pavillion at the World EXPO in Milan, 2015 stands tall next to other much larger countries and celebrates the culinary and agricultural heritage of the country. At the 1888 and 1889 World Expos, the father of Uruguayan wine, Don Pascual Harrigue won awards for his Tannat.

Tannat continues to be the hallmark grape of Uruguay, and also exists in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, and its native France. Its cultivation is taking on new dimensions as producers distinguish between “heritage” varieties descended from the first transplanted Basque cuttings and new “clone” varieties that are said to be more powerful in comparison. Come to Grand Cata to taste and compare with us sometime and decide for yourself!